CRIMES FOR POE: Part I - The Death of Edgar Allan Poe

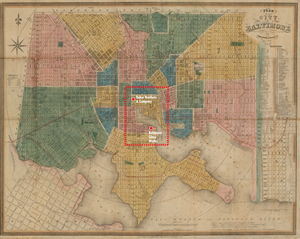

On the morning of October 3, 1849, at approximately 10:00 a.m., a printer for the Baltimore Sun newspaper, Joseph W. Walker, happened upon a disheveled man sitting on a sidewalk along East Lombard Street, between Exeter and High Streets in downtown Baltimore, Maryland. Walker immediately recognized the man as famed poet and author Edgar Allan Poe. Walker’s discovery of the enigmatic, incoherent Poe was, without contestation, the beginning of one of America’s most mysterious stories:

The Death of the Father of Modern Detective Fiction.

The inscrutable and talented Edgar Allan Poe had spent the summer of 1849 on a lecture tour to raise money for a proposed writer’s magazine, Stylus. In late May, he was in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for a brief time before traveling to Richmond, Virginia, where he stayed until September 27. Contemporary accounts of his final days in Richmond are scattered; however, it appears that Poe was preparing to travel to Philadelphia to edit the poetic works of Marguerite St. Leon Loud, titled Wayside Flowers (1851). He wrote a letter to his aunt Maria Clemm describing his travel plans for late September: “On Tuesday I start for Philadelphia to attend to Mrs. Loud’s Poems—& possibly on Thursday I may start for New York. If I do I will go straight over to Mrs. Lewis’s and send for you. It will be better for me not to go to Fordham—don’t you think so? Write immediately in reply and direct to Philadelphia For fear I should not get the letter, sign no name and address it to E.S.T. Grey Esqr . . . Don’t forget to write immediately to Philadelphia so that your letter will be there when I arrive.” The same day Poe wrote to Maria Clemm, he also wrote a letter to Loud explaining that he had been delayed, postponing his original departure date of September 7. He confirmed that he planned to be in Philadelphia on September 25 to begin editing her works.

The inscrutable and talented Edgar Allan Poe had spent the summer of 1849 on a lecture tour to raise money for a proposed writer’s magazine, Stylus. In late May, he was in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for a brief time before traveling to Richmond, Virginia, where he stayed until September 27. Contemporary accounts of his final days in Richmond are scattered; however, it appears that Poe was preparing to travel to Philadelphia to edit the poetic works of Marguerite St. Leon Loud, titled Wayside Flowers (1851). He wrote a letter to his aunt Maria Clemm describing his travel plans for late September: “On Tuesday I start for Philadelphia to attend to Mrs. Loud’s Poems—& possibly on Thursday I may start for New York. If I do I will go straight over to Mrs. Lewis’s and send for you. It will be better for me not to go to Fordham—don’t you think so? Write immediately in reply and direct to Philadelphia For fear I should not get the letter, sign no name and address it to E.S.T. Grey Esqr . . . Don’t forget to write immediately to Philadelphia so that your letter will be there when I arrive.” The same day Poe wrote to Maria Clemm, he also wrote a letter to Loud explaining that he had been delayed, postponing his original departure date of September 7. He confirmed that he planned to be in Philadelphia on September 25 to begin editing her works.

Poe researchers have advanced the idea that E.S.T. Grey, Esq., was a fictitious name used by the writer as one way to account for his paranoia, and Poe would only have done so because he was suffering from a long-term delusional state brought on by his alcohol and drug use. His actions around the time that he wrote his letter to Clemm tend to discount the thought that he was suffering from long-term effects from intoxicants. By available accounts, Poe had become a member of the Richmond branch of the Temperance Movement and had stopped drinking. He set about making plans to embark on the Stylus endeavor and had several lectures booked at the Exchange Hotel in Richmond.

Poe researchers have advanced the idea that E.S.T. Grey, Esq., was a fictitious name used by the writer as one way to account for his paranoia, and Poe would only have done so because he was suffering from a long-term delusional state brought on by his alcohol and drug use. His actions around the time that he wrote his letter to Clemm tend to discount the thought that he was suffering from long-term effects from intoxicants. By available accounts, Poe had become a member of the Richmond branch of the Temperance Movement and had stopped drinking. He set about making plans to embark on the Stylus endeavor and had several lectures booked at the Exchange Hotel in Richmond.

There is no question that Poe suffered greatly in the early part of June 1849; however, there is clear evidence through his writings that he was being plagued by something akin to a reoccurring seizure that would bring about unique psychological side effects such as depression, hallucinations, and uncontrollable fits of anger. Two letters that Poe sent to Clemm in June reflect that the condition from which he was suffering would come and go, leaving the writer confused about his actions. The first letter Poe sent to Clemm, dated June 7, 1849, describes a debilitating illness: “I have been so ill—¬have had the cholera, or spasms quite as bad, and can now hardly hold the pen.” The condition that Poe writes about had passed by mid-June, and he wrote a second letter to Clemm 12 days later, explaining the true state of his condition: “You will see at once, by the handwriting of this letter, that I am better—much better in health and spirits. Oh, if you only knew how your dear letter comforted me! It acted like magic. Most of my suffering arose from that terrible idea which I could not get rid of—the idea that you were dead. For more than ten days I was totally deranged, although I was not drinking one drop; and during this interval I imagined the most horrible calamities . . . All was hallucination, arising from an attack which I had never before experienced—an attack of mania-a-potu. May Heaven grant that it prove a warning to me for the rest of my days. If so, I shall not regret even the horrible unspeakable torments I have endured.”

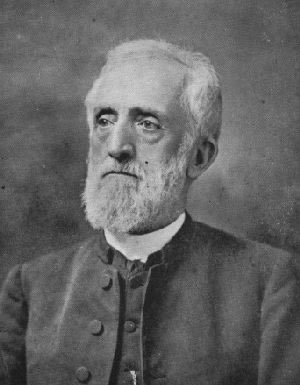

Oscar Penn Fitzgerald, author, newspaper editor, and a bishop of the Methodist church had the occasion to encounter Edgar Allan Poe in late summer of 1849. His recollections on the meeting, published in Bishop Fitzgerald’s Life Story, do not paint a picture of a downtrodden, drunken, and longsuffering poet: “I have a very vivid impression of him as he was the last time I saw him, on a warm day in 1849. Clad in a spotless white linen suit, with a black velvet vest and a Panama hat, he was a man who would be notable in any company. I met him in the office of the Examiner, the new Democratic newspaper which was making its mark in political journalism.” Fitzgerald went on to describe Poe’s outward appearance on that day. “Through the good offices of certain parties well known in Richmond, Poe had taken a pledge of total abstinence from all intoxicating drinks. His sad face—It was one of the saddest I ever saw—seemed to brighten a little, as a new purpose and fresh hope sprang up in his heart.” In relation to his writing abilities, Fitzgerald goes on to explain that before leaving Richmond, Poe held a lecture on his essay The Poetic Principle. The lecture packed the meeting rooms of the Exchange Hotel, with 300 patrons paying $5 apiece. Fitzgerald recounted, “I had the pleasure of hearing it read, and remember how forcibly I was struck with his tone and manner of delivery.” His recollection does not evoke a man who was delusional, paranoid, or suffering from the long-term effects of alcohol. In contrast, this account by Bishop O.P. Fitzgerald describes a man who was clear in thought and basking in his literary success.

Oscar Penn Fitzgerald, author, newspaper editor, and a bishop of the Methodist church had the occasion to encounter Edgar Allan Poe in late summer of 1849. His recollections on the meeting, published in Bishop Fitzgerald’s Life Story, do not paint a picture of a downtrodden, drunken, and longsuffering poet: “I have a very vivid impression of him as he was the last time I saw him, on a warm day in 1849. Clad in a spotless white linen suit, with a black velvet vest and a Panama hat, he was a man who would be notable in any company. I met him in the office of the Examiner, the new Democratic newspaper which was making its mark in political journalism.” Fitzgerald went on to describe Poe’s outward appearance on that day. “Through the good offices of certain parties well known in Richmond, Poe had taken a pledge of total abstinence from all intoxicating drinks. His sad face—It was one of the saddest I ever saw—seemed to brighten a little, as a new purpose and fresh hope sprang up in his heart.” In relation to his writing abilities, Fitzgerald goes on to explain that before leaving Richmond, Poe held a lecture on his essay The Poetic Principle. The lecture packed the meeting rooms of the Exchange Hotel, with 300 patrons paying $5 apiece. Fitzgerald recounted, “I had the pleasure of hearing it read, and remember how forcibly I was struck with his tone and manner of delivery.” His recollection does not evoke a man who was delusional, paranoid, or suffering from the long-term effects of alcohol. In contrast, this account by Bishop O.P. Fitzgerald describes a man who was clear in thought and basking in his literary success.

On the eve of his departure from Richmond, Poe visited the home of physician Dr. John R. Carter, a lifelong friend of the Poe family. Upon leaving Dr. Carter’s office, the writer left a copy of Thomas Moore’s Irish Melodies, often misidentified as Irish Rhapsodies, and mistakenly picked up Carter’s rattan cane, which concealed a sword. Dr. Carter’s impression of Poe’s lecture on The Poetic Principle echoes that of Bishop Fitzgerald, and both men attest that Poe was in possession of $1,500 when he departed Richmond. In 1849, 1,500 US dollars were worth approximately $42,000 against the 2015 US dollar. Understandably, some Poe researchers believe him to be the target of a mugging and beating that would have left him in a disheveled state on Lombard Street six days after he departed for Philadelphia.

Edgar Allan Poe left Richmond bound for Philadelphia on the night of September 27. The most reputable account of Poe’s travels places him on board of a ship sailing from Richmond to Baltimore, where he would catch the train to Philadelphia. Poe’s whereabouts for the next six days have become the stuff of legend, as there is no practical theory that can explain where he was, who he was with, what he may have endured, or how he came to be on a Baltimore street. Neilson Poe, who was married to Josephine Clemm, the sister of Poe’s wife, Virginia, wrote a letter from Baltimore, dated several days after Poe’s death. He claimed that “where he [Poe] spent the time while he was here, or under what circumstances, I have been unable to ascertain.”

Due to his literary successes in the 1840s, Poe was a prominent figure in most northeastern cities in which he traveled. When Walker made his fateful discovery, Poe was not impeccably dressed in his trademark black coat and black velvet vest. In contrast, he was wearing a dirty and worn-out sack coat, unpolished shoes that were worn down at the heel, and a ragged straw hat. His face and clothing were covered in dirt, and he had a hint of whisky on his breath. In a very strange twist to the descriptions of Poe’s condition, he was found on Lombard Street, holding the very expensive and identifiable cane of Dr. Carter. To Walker, Poe appeared to be intoxicated or in some state of delirium, as the writer spoke incoherently and maintained an uncompromising state of lassitude. Walker recognized that Poe was in dire trouble and helped the feeble man into a tavern at 44 East Lombard Street, which belonged to Cornelius Ryan. Often referred to as Gunner Hall, Ryan’s Tavern was a polling location for Baltimore’s Fourth Ward, and the day that the famed troubadour was found was voting day in Maryland. Although the weather in Baltimore was rainy on that Wednesday, Ryan’s Tavern, and ostensibly Lombard Street, were bustling with people traveling to and from the polls.

Once Walker settled Poe at a table in Ryan’s Tavern, he asked the wavering patient if there was anyone that he should contact. Through his haziness, Poe said the name of at least one person—Dr. Joseph Evans Snodgrass, a physician, editor, and leader of the Temperance Movement in Baltimore during the 1840s. Walker sent a letter to Dr. Snodgrass, which read:

“Dear Sir, There is a gentleman, rather the worse for wear, at Ryan’s 4th ward polls, who goes under the cognomen of Edgar A. Poe, and who appears in great distress, & he says he is acquainted with you, and I assure you, he is in need of immediate assistance, Yours, in haste, Jos. W. Walker.”

When Snodgrass arrived, he was accompanied by Henry Herrin, the husband of Poe’s aunt Elizabeth Poe Herring. The two men deduced that Poe, who had been sober for some time due to his pledge, had gone on an alcohol-fueled bender and declared the writer to be drunk. His uncle Henry Herring, who had his own animosities toward Poe, refused to take him to his home to care for him. Joseph Snodgrass, Joseph Walker, and Henry Herring loaded the semiconscious writer into a carriage bound for Washington University Hospital, located on Baltimore’s Washington Hill.

At Washington University Hospital, Poe was placed in a room normally reserved for people who had fallen ill from consuming alcohol; however, his attending physician, Dr. John J. Moran, did not believe that the writer was drunk or suffering from an alcohol-induced calamity. In accordance with the symptoms Poe exhibited, the 25-year-old Moran, who had received his degree from the University of Maryland in 1845, believed that Poe had been the victim of a physical attack, during which he had sustained significant head trauma. This supposed assault would have left his famous patient sufficiently disoriented and lethargic. Moran, as the only witness to Edger Allan Poe’s condition during the days prior to his death, stated that he had offered brandy to the patient in an attempt to calm him, but the beverage was staunchly refused. He questioned Poe on several occasions in an attempt to ascertain what had befallen him, but no explanations for the six days prior were to be had from the disoriented man. In the years that followed Poe’s death, Moran stated that Poe, clearly in a deteriorating state, would go into fits of dark, foreboding language that made very little sense to the physician. He would maintain within lectures and his writings on the subject of Poe’s death that Poe’s wild rants included, “Language cannot tell the gushing well that swells, sways and sweeps, tempest-like, over me, signaling the larm of death,” and “My best friend would be the man who gave me a pistol that I might blow out my brains.” Through the years, Moran’s stories of Poe tended to vary; however, the physician stood his ground and maintained his famous patient did not suffer from an alcohol-related event. He noted in a lecture many years after the artist’s death: “I have stated to you the fact that Edgar Allan Poe did not die under the effect of any intoxicant, nor was the smell of liquor upon his breath or person.”

On Thursday, October 4, Neilson Poe arrived at the hospital in an attempt to visit the ailing poet. He was told that the patient was too excitable to see him. Neilson Poe left the hospital, only to return the next day. He describes his actions in relation to the events in a letter to Maria Clemm dated October 11, 1849:

“As soon as I heard he was at the college, I went over, but his physicians did not think it advisable that I see him, as he was very excitable. The next day, I called and sent him changes of linen, etc.”

Edgar Allan Poe lay in a lonely, semi-dark room on the second floor of the Washington University Hospital for four long days, drifting in and out of consciousness and speaking to imaginary entities within his room. Moran had no way of knowing that in 1847, Poe was diagnosed by Dr. Valentine Mott of New York, as having lesions on his brain, and Dr. John Francis had diagnosed the author with a weak heart in 1848. Because of these two conditions, which were unknown to Moran, he could not ascertain the cause of his peculiar patient’s condition and was unable to render any type of relief. He watched helplessly as Poe slowly slipped deeper and deeper into his condition. Moran later stated, “When I returned, I found him in a violent delirium, resisting the efforts of two nurses to keep him in bed. This state continued until Saturday evening when he commenced calling for one ‘Reynolds,’ which he did through the night up to three on Sunday morning.” Several hours later, at around 5:00 a.m., Edgar Allan Poe was dead. Neilson Poe, who had tried to ease the suffering of his famous cousin through fellowship and clean, fresh linens mourned, “And I was never so shocked, as when, on Sunday Morning, notice was sent to me that he was dead.”

“Our city was yesterday shocked with the announcement of the death of Edgar A. Poe, Esq., who arrived in this city about a week since after a successful tour through Virginia, where he delivered a series of able lectures. On last Wednesday, election day, he was found near the Fourth ward polls laboring under an attack of mania a potu, and in a most shocking condition. Being recognized by some of our citizens he was placed in a carriage and conveyed to the Washington Hospital, where every attention has been bestowed on him. He lingered, however, until yesterday morning, when death put a period to his existence. He was a most eccentric genius, with many friends and many foes, but all, I feel satisfied, will view with regret the sad fate of the poet and critic.”

—The New York Herald, October 9, 1849

A Baltimore newspaper, Clipper, had heralded death of Edgar Allan Poe on October 8, 1849, by announcing that he had died of “congestion of the brain.” Researchers have long attributed Poe’s congestion of the brain as an after effect of the writer’s alcohol use, but this diagnoses are, at best, misdirected. It is common knowledge that Poe was a chronic alcoholic, and long-term alcoholism can affect the brain, but early-19th-century scientists used congestion of the brain to describe numerous then-inscrutable conditions, from epilepsy to stroke. Dr. William A. Hammond, who dedicated his life to the study of neurological diseases, separated alcoholism, Grave’s disease, opiate poisoning, typhus, and other types of viral diseases from his study of diseases of the brain in A Treatise on Diseases of the Nervous System. First published in the Journal of Psychological Medicine in 1871, Hammond describes swelling of the brain from long term alcoholism as an after effect of the alcoholism and not an actual brain disorder that causes death. This assertion hints that Poe died from an actual brain disease such as epilepsy, encephalitis, hydrocephalus, or meningioma, which is a slow-growing calcified mass that develops in the membrane between the skull and the brain. Furthermore, Poe had been alcohol free for at least four, and possibly six months. This one fact, and Dr Hammond’s contemporaneous study of the human brain, undermines the theory that he had literally drank himself to death.

The funeral of Edgar Allan Poe was not a grand affair that lavished praise and honorifics upon the enigmatic writer as his body passed through the streets of Baltimore. In fact, it was a much smaller affair, with only nine people in attendance on October 8, 1849. At approximately 4:00 p.m. on that day, renowned author and the “Father of Modern Detective Fiction” was laid to rest in an unlined mahogany coffin within an unmarked grave near his grandfather David Poe Sr. in the Westminster Presbyterian Church graveyard, on the corner of West Fayette and North Greene Streets.

In 1873, a school teacher from Baltimore, Sara S. Rice, began to gather money for a proper monument for Edgar Allan Poe, who, in death, had become a literary giant. Two years after the monument was erected, officials of Westminster Presbyterian decided to move Poe’s remains to a new burial site closer to the front of the churchyard. During that move, George W. Spence, the sexton who oversaw the first burial of Poe, reported that the author’s skeletal remains were in excellent shape; however, when he picked up Poe’s skull, a hard, calcified mass was found rolling around inside of the cavity. Spence reported, “[H]is brain rattled around inside just like a lump of mud.” Another witness who relayed the story of Poe’s exhumation to a Baltimore newspaper relayed, “[T]he cerebral mass, as seen through the base of the skull, evidenced no signs of disintegration or decay, though, of course, it is somewhat diminished in size.”

The calcified mass discovered inside of Edgar Allan Poe’s skull, in 1875, may be the definitive clue as to the cause of the author’s death. Unfortunately, this, and undisputedly, all of the theories surrounding his death, fall into to the dubious category of conjecture. Maybe Poe was beaten so badly for his money that the head trauma sent him into a state of delirium that would inevitably cause his death. There is compelling evidence to suggest that such an event could have occurred. He could have consumed so much alcohol and opiates during his lifetime that the blood vessels in his brain ceased to function properly, eventually killing him. It is possible, but the probability of such an event has always been in question by the medical community. A brain tumor such as meningioma that created extreme hallucinations and bipolar disorder–like symptoms could have caused him to black out for six days, depositing Poe on a Baltimore street, and eventually, his death bed. Unsupported documentation from the time of his exhumation seems to support such a scenario, or perhaps Poe died of something deeper, darker, and beyond the understanding of modern-day professional, and amateur, Poe researchers. Poe enthusiast and history book editor Abigail Fleming has stated that he may have died from “long-term untreated illness, alcoholism, and a tortured, unfulfilled soul.” Although gentle in its delivery, her theory is as plausible as beatings, tumors, and now-common diseases that were misdiagnosed. Furthermore, of all of the theories that have been proposed in the last 165 years, her theory is the most Poe-esque.

The Father of Modern Detective Fiction left the world with many great works of the Romantic era, but moreover, he left behind one of the greatest mysteries in United States history: